The Wild Men

The United States of America has some of the most efficient public transportation systems in the world. New York has a spectacularly complex subway system, with the A, B, C, N, R, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 trains. Washington's network is more luxurious and also very slightly more imaginatively named - the lines are called the Red line, the Blue line, the Green line, and so on. But my favorite is the O-line, which is short for the Orang-line (that's "Orang," not "Orange"). It runs thirty feet above the ground and does not carry any trains at all. The O-line consists of two thick ropes, about four feet apart, stretched along tall posts. It is designed not for humans, but for orangutans, and it runs across the width of the magnificent National Zoo. Wherever it crosses the public walkway there is a sign that reads "O-LINE: BE CAREFUL, ORANG XING."

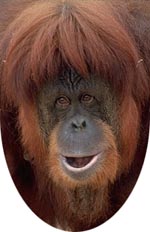

Orangutans, for the benefit of the unaware, are large red apes from Borneo and Sumatra. The O-line links their enclosure in the zoo to a building called the Think-Tank. There, the orangutans can engage in a host of mentally stimulating activities. For the public, it presents a chance to see the extraordinary intelligence of these large, human-like primates.

The human-like primates are being treated as more and more human-like all the time. Chimpanzee tea parties may be a thing of the past, but there are now more serious moves to narrow the gap between apes and men. Chimpanzees and gorillas have been taught rudimentary sign language. The New York Times Weekly Review (August 22, 1999) ran an article about a growing group of lawyers and legal academics who are plotting strategies to bring a Great Ape Suit to court. It voiced the following prediction:

"A great ape will appear in the courtroom. A lawsuit, perhaps protesting the ape's life behind bars, will have been filed in the animal's name. The ape will then testify in sign language or using a voice synthesizer to support the claim that, contrary to centuries of law, it has legal rights, including a fundamental right to liberty." The New York Times continued to say that "in essence, the lawyers want to challenge the status quo by asking the courts to look closely at great apes, large and intelligent creatures like gorillas, chimpanzees and orangutans that resemble humans genetically."

Despite the concept appearing utterly ridiculous, many will find it unnerving. Whether the suit will succeed or not, it is bound to raise considerable controversy. Darwinian evolutionists and religious people alike think that discussions of similarities between apes and men, and especially discussions of ape-men, threaten religion. Thus, evolutionists have proudly spoken of the tests that have shown 99% genetic similarity between humans and chimpanzees, while religious people exorcise Neanderthal man from the textbooks.

Now prepare yourself for a shock.

Without getting into the issue of whether or not we are actually descended from apes, Judaism has been discussing the similarities for a very long time indeed. Orangutans in particular have been the subject of debate in Jewish Law for over two thousand years. Remarkably, there is discussion as to whether they share certain laws with humans! Well before O-Lines and Think-Tanks were constructed, Jewish law had perceived the humanlike qualities of great apes and was debating just how humanlike their legal situation should be.

The Mishnah (Kilayim 8:5) states: "Adnei ha-sadeh is rated as an animal. Rabbi Yosi says: It causes spiritual impurity (when dead) in a building, like a human being."

What is the adnei ha-sadeh? The Talmud (Talmud Yerushalmi, Kilayim 8:4) elaborates: "Adnei ha-sadeh, the yaysi-araki, is the mountain-man."

Curiouser and curiouser. What is the mysterious mountain-man? The answer isn't entirely clear, but Rabbi Yisrael Lifshitz, a nineteenth-century commentary on the Mishnah, provides the following explanation:

Curiouser and curiouser. What is the mysterious mountain-man? The answer isn't entirely clear, but Rabbi Yisrael Lifshitz, a nineteenth-century commentary on the Mishnah, provides the following explanation:

"It seems to me that it means the 'wildman' which is called 'orangutang.' This is a type of large ape, genuinely similar to a person in form and build, except that its arms are long, reaching to its knees. It can be taught to chop wood, to draw water, and also to wear clothes, just like a human being; and also to sit at a table and eat with a knife, fork and spoon. In our times, it is only found in the great jungles of Africa; however, it appears that it may formerly have been found also in the vicinity of the Land of Israel, in the mountains of Lebanon, where even in our day there are great forests, of the 'cedars of Lebanon' fame; and therefore it was called 'the mountain-man'." (Tiferet Yisrael ad loc.)

The term adnei hasadeh, explained to mean "men of the field" (see Encyclopedia Talmudit), may well also include other great apes. The Malbim (Vayikra 11:27) states that it refers to chimpanzees as well as orangutans. Rambam notes that "those who bring news from the world state that it speaks many things which cannot be understood, and its speech is similar to that of a human being." This description would be adequately accurate for all of the great apes. Of course, it may refer to a different creature. The Torah prohibition against eating blood is said by the Midrash not to include two-legged creatures. The use of this term, as opposed to it simply saying "man," is taken to include the adnei ha-sadeh, described as walking on two legs like a man. Does this refer to the great apes, which occasionally walk in this posture, or to some other creature? Was there some form of Neanderthal man extant in those days? Or does it refer to a creature unknown to modern science, such as Bigfoot, the yeti, or the sasquatch? For the time being, the best we have to go on is Rabbi Lifshitz's definition of the orangutan.

Remarkably, then, we have a two thousand year old discussion in Jewish law concerning the similarities between orangutans and humans. The debate in the Mishnah as to whether it is rated as an animal or as a human has several ramifications in Jewish law. One, whether their corpses cause tum'ah (spiritual impurity), is mentioned in the Mishnah. Another ramification, mentioned by Rambam, concerns a person who sells "all of his animals." If the adnei ha-sadeh are rated as humans, then they are not included in such a sale. (Such a matter could be highly relevant to those zoos in Israel which sell of their animals to a Kohen, such that they can eat the terumah produce which the zoos receive free from the local Religious Council.)

We see here very clearly that it's not ridiculous to group apes with men for certain aspects. This should also be a lesson to us not to make any assumptions about what the Torah perspective on various issues actually is. Nevertheless, it is incorrect (although perhaps not utterly ridiculous) to group apes together with humans for matters such as legal rights. There would seem to be no Torah basis for that, and the very line of thought is based on a misconception. The New York Times writes that "modest cases, some animal-rights lawyers, say, could set the stage for ambitious suits like a great ape case. Some legal scholars, for example, are considering whether the legal system can justify common but arguably cruel farming practices, like the close confinement of animals raised for slaughter." This line of thinking is seriously flawed from a Torah perspective. It is true that many farming practices are cruel and wrong. However, they are wrong not because they impinge on any animal rights, but rather because they are inconsistent with human obligations. Solving the mistreatment of animals is not to be achieved through granting rights to animals, but rather through reinforcing moral obligations of people.

Let's hope that equal rights for apes remains a fantasy. Still, if your daughter comes home one day and tells you that she's met the guy of her dreams, and she adds that he's dark and strong and is involved in medical research, you might want to prepare for the fact that he might not be a Jewish doctor.