The Kiss of Death

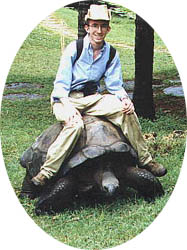

The giant reptile paused in its tracks upon seeing me. It stared at me out of huge eyes that were black as coal as I tentatively reached out my hand to scratch its chin. Then, deciding that I presented no threat -- after all, I was only a quarter of its size -- it carried on walking. I quickly moved out of its way to prevent being crushed by its great weight. Then I climbed onto its back for a unique ride through the African jungle.

The giant reptile paused in its tracks upon seeing me. It stared at me out of huge eyes that were black as coal as I tentatively reached out my hand to scratch its chin. Then, deciding that I presented no threat -- after all, I was only a quarter of its size -- it carried on walking. I quickly moved out of its way to prevent being crushed by its great weight. Then I climbed onto its back for a unique ride through the African jungle.

The guide told me that this was one of thirteen giant tortoises in Kenya. They had been washed ashore several decades earlier, after having fallen off ships that had taken them from their home in the Seychelles islands to use as food. He estimated their age at close to two hundred years.

This unique experience came to mind when surveying parashas Chayey Sarah, "the life of Sarah." The title of the parashah would seem to reflect a singular lack of good taste, as it begins with the end of the life of Sarah. It then proceeds to discuss the purchase of her burial plot (from which we learn the laws of kiddushin) and the later ageing and subsequent death of Avraham.

Aside from the unfortunate title, the concepts of ageing and death, which are the themes of this parashah, are also difficult to understand. Why should people age? It's not as ridiculous a question as it sounds if you've studied tortoises. For certain tortoises don't age. They just get older and older and older, without showing any decline in physical or mental faculties, until eventually they are overtaken by some disease or another. The ageing process, according to a recent issue of National Geographic, seems to be linked to a specific set of genes that tortoises don't possess.

In experiments on fruit flies, scientists have managed to counteract the ageing effect, causing the flies to live some thirty times longer than their usual life expectancy. If they ever find a way to do that for humans, we'll be living for more than two thousand years.

Perhaps the longer life-spans of humans before the Great Flood was due to an absence of these genes. But in any event, why do we have them? Ageing is a process that is bitterly resented and fought by almost everyone. After National Geographic published its article, containing a graphic depiction of the ways in which the body deteriorates throughout adulthood, they received a number of letters from people protesting that they didn't want to become depressed by reading about how they are wasting away. Why does it happen?

The Chafetz Chaim used to speak about the Immortals Club, a society that has millions of members worldwide. These are people who believe that they are going to live forever. Of course, they will profess to acknowledge that everyone dies eventually. But to all practical intents and purposes they don't actually think that it's going to happen to them.

Why do they blind themselves to the fact of mortality? Because it interferes with their plans. Most people are obsessed with pursuing material pleasures, financial security, and other such goals that are limited to this world alone. Their soul plays a tertiary role to their body. Hence, people consider their twenties and thirties to be their prime, their heyday. The fortieth birthday presents a mid-life crisis, their forties and fifties are spent fighting the ageing process, and after that they go into a decline.

For the person who lives life with his soul as his highest priority, things proceed somewhat differently. Avraham was well over a hundred years old when he was described as a person who was "ba bayamim," which according to the Kli Yakar means "coming into his heyday." He wasn't past his prime, he was just entering it.

Ageing is a kindness. The young person is too easily caught up with his body and with material goals. The ageing process reminds him that he isn't going to live forever, and that only spiritual accomplishments are going to accompany him to the next world. He is reminded to increase his study of Torah and his fulfillment of mitzvos, things that he can take with him.

Spiritual accomplishments increase with added age. The Torah does not consider the elderly person to be a fogey or a fuddy-duddy. He is a zaken, which is an acronym for zeh kanah chachmah -- "this one has acquired wisdom." He has seen the best of times and the worst of times, and these afford him a uniquely broad perspective on things. "Rav Yochanan would stand up [even] in the presence of elderly Arameans (non-Jews), and say: Imagine the experiences that these people have passed through!" (Kiddushin 33a).

Armed with the wisdom of experience, focused on spiritual pursuits, the zaken is able to work towards the next stage of his life. It has been noted that there are many parallels between death and marriage. We already noted that the laws of kiddushin are learned from the purchase of a burial plot. The day of entry into both is a quasi Yom Kippur for which one dresses in white; they are both followed by seven-day periods.

Armed with the wisdom of experience, focused on spiritual pursuits, the zaken is able to work towards the next stage of his life. It has been noted that there are many parallels between death and marriage. We already noted that the laws of kiddushin are learned from the purchase of a burial plot. The day of entry into both is a quasi Yom Kippur for which one dresses in white; they are both followed by seven-day periods.

Some would use these parallels for repugnant jokes that compare marriage to death. But the truth is that death is to be compared to marriage. In marriage, one enters into a more advanced stage of life, which is a relationship with another. In death, too, one enters a more advanced stage of life in which one consummates a relationship with another -- God.

It is no coincidence that fall, the time of year in which the natural world dies away, is the time of year in which we celebrate Sukkos and Shemini Atzeres. These festivals represent the consummation of the relationship between God and the Jewish people. Such a relationship can only occur when the physical world has been suitably negated.

The Gemara (Berachos 8a) tells us that with the finest form of death, termed "the kiss," the life departs from this world as easily as a hair being lifted from a saucer of milk. The story of told of a certain rabbi on his deathbed who was surprised to see his students weeping. "Why are you sorry for me?" he asked them. "All my life, I have been preparing for this moment!"

The parashah of "the life of Sarah" does not speak of the ending of her life. The passuk speaks of the end of "the years of the life of Sarah." These numbered only one hundred and twenty-seven full and satisfactory years. But her life continued for an eternity beyond that. "Tzaddikim b'misasam keruyim chayyim -- The righteous even after their deaths are called 'living'."

Sources:

• Bereishis Rabbah 58:1, 65:9.

• Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsch, Bereishis 23:1.