Going Extinct?

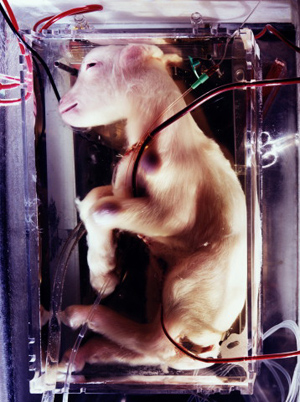

Later this month, an extraordinary event is due to take place: a cow will give birth in Iowa. Cows give birth all the time, especially in Iowa, but the difference is that this cow is not giving birth to another cow, but rather to a gaur.

Gaurs are huge ox-like animals from Asia that are highly endangered. Formerly hunted for sport, they now suffer from habitat loss and could soon be extinct. A novel attempt is now being made to save the gaur by cloning them, thereby enabling ordinary cows to produce new gaurs. The first gaur, destined to be born this month, is due to be named Noah (although perhaps a better choice of name would be Al).

Gaurs are huge ox-like animals from Asia that are highly endangered. Formerly hunted for sport, they now suffer from habitat loss and could soon be extinct. A novel attempt is now being made to save the gaur by cloning them, thereby enabling ordinary cows to produce new gaurs. The first gaur, destined to be born this month, is due to be named Noah (although perhaps a better choice of name would be Al).

Other rare animals, too, are scheduled for cloning, including the bongo, cheetah, Sumatran tiger, and, of course, the giant panda. It might even be possible to bring back an animal that is already extinct. The last bucardo, a mountain goat from Spain, died of a smashed skull when a tree fell on it early this year, but scientists have preserved some of its cells. It is not a straightforward procedure, however, as even if there are remaining surviving animals, they are too rare to be used as host mothers. This means that similar species must be persuaded to accept the cells of the clones - by no means a simple process. Six hundred and ninety-two attempts were necessary to produce the gaur clone. What's the point? Why spend so much effort and expense to save one species? What difference does it make if it becomes extinct? Why is conservation important?

One answer is that animals can prove to have extraordinary uses to human beings. Scientist Michael Zasloff discovered that African clawed frogs secrete antibiotics; he named these substances mageinins, after the Hebrew word magen, "shield." Cancer fighting molecules are obtained from the liver of the dogfish shark; similar substances are found in chonemorpha macrophylla, a climbing plant that grows from Java to the foothills of the Himalayas. Even the most obscure animals and plants can have an important function.

Yet this answer is limited in its application. The January edition of National Geographic, discussing the extensive efforts to save some of the 1,100 species of endangered birds from extinction, raised this difficulty. Writer Virginia Morell interviewed Stuart Pimm, a man working to save the entirely unremarkable Cape Sable sparrow. She admitted the dilemma: "The Cape Sable sparrow, of course, is not likely to lead to a cure for cancer or to any other earthshaking discovery. Nor are most species around us. Why would it matter if this little bird, or any of the 1,100 others on Pimm's list, became extinct?" Morell left this question unanswered. And there doesn't seem to be any good answer. How can one justify the vast effort that is required to save obscure animals from extinction? With the latest advances in genetic technology, this question becomes even more potent. The current issue of Scientific American raises the concern that the new cloning technology will actually further hasten the destruction of animals and their environment. This is because once it becomes possible to clone an animal, there will be less incentive to actually do so. Why go to the trouble of maintaining a population in its natural habitat, when it can be preserved as DNA samples in a freezer? It is easy to imagine that conservation efforts would lose support once Cape Sable sparrow DNA can be preserved and kept for the rare chance that it may prove useful in the future. We might have a gut feeling that it is nevertheless important to preserve the natural world, but how can we rationally justify this?

From a theological standpoint, different factors come into the picture. The Bible prohibits taking both a mother bird and her young from the nest: "If you happen across a bird's nest... Do not take the mother bird together with the children" (Deuteronomy 22:6). The thirteenth century scholar Nachmanides explained that taking a mother bird together with its young means destroying two generations of animal life and leaving no possibility of future descendants from either. This indicates that one does not care for the perpetuation of the species and is therefore forbidden. But why is it so important to care for the perpetuation of the species? The answer is alluded to in a statement of King Solomon: "Look at the work of G-d, for who can rectify that which he has damaged?' (Ecclesiastes 7:13)." The Midrash explains: "At the time when G-d created Adam, He took him around the trees of the Garden of Eden, and He said to him, 'Look at My works, how beautiful and praiseworthy they are! Everything that I created, I created for you; take care that you do not damage and destroy My world, for if you damage it, there is no one to repair it afterwards!' " (Midrash Koheles Rabbah 7).

If the world is some sort of random accident, then there is little reason to save animals from extinction. That is to say, there is a very little reason - the small odds that it may prove to have some vital use for man - but with modern cloning technology, all we need to save is its DNA. However, if one believes that the universe was created for a purpose, then everything in it is precious. The Midrash spells this out: "Even things which appear to you to be superfluous in the world, such as flies, fleas and mosquitoes, they are also part of the creation of the world, and G-d performs His operations through the agency of all of them, even through a snake, mosquito or frog" (Midrash Bereishis Rabbah 10:7). Sometimes their purpose may be obvious, such as with the African clawed frog. But even when no purpose is apparent to us, we can be sure that one nevertheless does exist. The animal did not just happen; it was meant to be. G-d intended for there to be such a creature - we have no right to wipe it out.

Stuart Pimm, the man working so hard to save the Cape Sable sparrow, seems to be aware, at some level, that conservation is ultimately only meaningful from a religious perspective: "I think we must ask ourselves if this is really what we want to do to G-d's creation. To drive it to extinction? Because extinction really is irreversible; species that go extinct are lost forever. This is not like Jurassic Park. We can't bring them back."

True, we can't bring back animals that became extinct a long time ago, such as dinosaurs or woolly mammoths, because there is no DNA left to work with. But it now seems possible to freeze DNA from animals that still have some surviving members, such that we can allow them to become extinct, safe in the knowledge that we can bring them back if we ever wish to do so. In that case, only if we accept that the natural world is G-d's handiwork will we have reason to preserve it.

Postscript:

It turned out that National Geographic wasn't adequately explicit on Professor Pimm's views, as I discovered from an email that I later received:

Dear Rabbi Slifkin,

A close Jewish friend, a distinguished ecologist, sent me something I believe you wrote about me. I greatly enjoyed what you wrote and have filed its examples for future use. My only regret is that you added "at some level." I'm not Jewish, but Episcopalian: I would have been quite happy for you to have written, "Stuart Pimm is aware that conservation is ultimately only meaningful from a religious perspective."

I agree entirely with your views that the utilitarian arguments have limited applicability: the rainforests may or may not harbor the cure for cancer, but it's very unlikely that the Cape Sable sparrow - or anything else in the Everglades for that matter - will provide a miracle cure for anything.

My best wishes,

Stuart Pimm

Professor of Conservation Biology

Center for Environmental Research and Conservation

Columbia University

My apologies to Professor Pimm for having misrepresented him, and my thanks to him for writing, and for further confirming the point of the essay: conservation is ultimately justified only from a religious perspective!

A much longer version of this essay can be found in the book Man & Beast. Click here for more details.